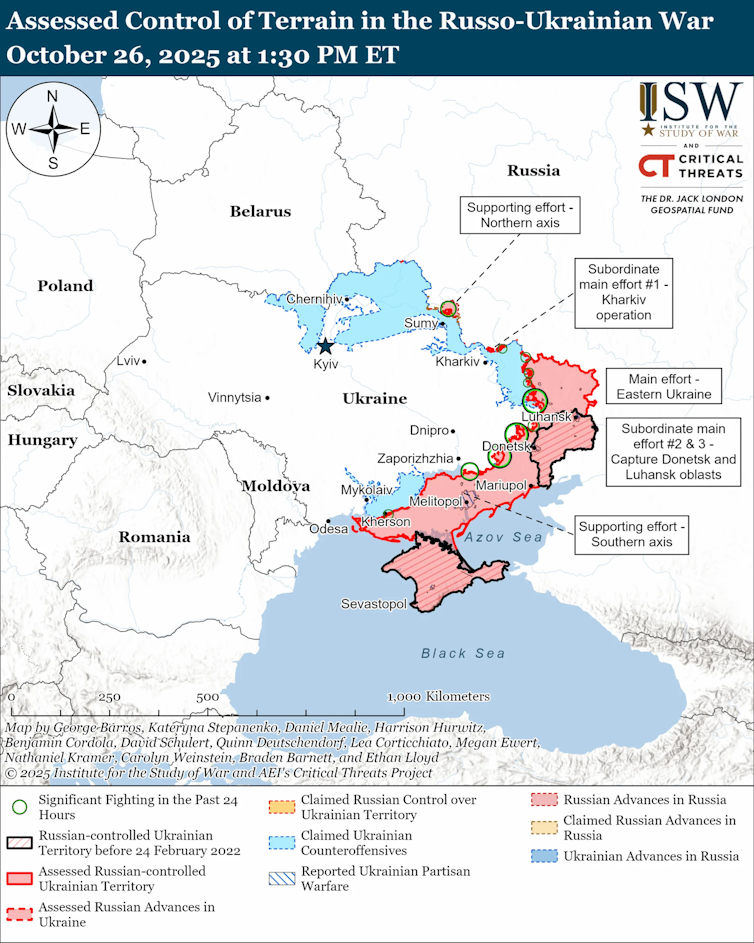

Following another week of diplomatic flip-flopping in the United States, Ukraine’s European allies did not disappoint when it came to the fulsomeness of their diplomatic rhetoric. Yet concrete action to strengthen the capabilities Ukraine needs to win the war remained at a snail’s pace.

After a less than successful meeting in the White House on October 17 between the American and Ukrainian presidents, Donald Trump and Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine and its European allies once again scrambled to respond to US equivocation with public affirmations of support for Kyiv.

A meeting of EU foreign ministers on Monday October 20, a summit of EU leaders on Thursday October 23, and a gathering of the coalition of the willing on Friday October 24, provided plenty of opportunities for such statements. For good measure, the Nato secretary general, Mark Rutte, paid a visit to Washington on October 21 and 22 before joining the leaders of the coalition of the willing on Friday.

The core message from all these meetings was that where the Trump administration sends ambiguous signals, Ukraine’s more steadfast European supporters are still keen to demonstrate their mettle.

When they met on Monday in Brussels, EU foreign ministers had a packed agenda. On Ukraine, the EU’s foreign affairs chief, Kaja Kallas, reiterated the bloc’s support for what she described as “Trump’s efforts to end the war” and condemned Russian attacks on Ukrainian energy infrastructure.

The following day, Tuesday October 21, brought diplomatic whiplash, when it transpired that there had been another apparent shift in the White House. The Budapest summit between Trump and his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, was postponed until further notice. The supposed host, Hungary’s Kremlin-friendly prime minister, Viktor Orban, and Putin’s spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, maintained that preparations for the meeting were continuing. But Trump was unequivocal. He would not waste time on a meeting if a peace deal was not a realistic prospect.

In an unusual moment of clarity, the US president then appeared to realise that he needed to demonstrate actual consequences for Russia obstructing a peace agreement. On October 22 the US announced sanctions on two of Russia’s largest oil companies – Rosneft and Lukoil – the first sanctions package imposed on Russia in Trump’s second term.

There is a grace period until November 21 to allow for the necessary winding down of transactions with, and divestment from, the two companies. Nonetheless, the mere announcement of the sanctions has already led to major Indian and Chinese clients beginning to pull out from their deals with Russia’s energy giants. Additional sanctions against the Russian banking sector and companies involved in oil infrastructure are apparently also being contemplated in the White House.

After much deliberation to overcome internal divisions, the EU followed suit. On October 23, it announced its 19th package of sanctions against Russia. This also targeted an oil trader and two refineries in China and banks in Central Asia.

In addition, the EU confirmed that a decision had been taken on the rules of the transition to a complete ban on any Russian gas imports. This will take full effect at the end of 2027.

All these efforts are critical to increasing pressure on Russia and are long overdue. But their immediate effect is uncertain. Russia has responded with the usual performative defiance. It has tested a new nuclear-powered missile and carried out a readiness drill for the country’s nuclear forces, overseen directly by Putin.

More help needed

With Russia’s air and ground wars against Ukraine continuing unabated, the other major challenge for Kyiv’s allies is providing assistance.

Here, progress has stalled. The US continues to withhold permission for Ukraine to use long-range missiles against targets deep inside of Russia. The mooted supply of Tomahawk missiles to Ukraine by the US has been scotched. Meeting with coalition leaders on Friday, Zelensky kept pressing for deep-strike weapons, stressing that when the US threatened to supply Tomahawks to Ukraine, Putin was willing to negotiate.

Even more pressing is the issue of how to cover Ukraine’s financial needs. Kyiv’s most recent estimate of the country’s unmet external financing needs for 2026-27 stands at US$60 billion (£45 billion).

At the European Council meeting on October 23, leaders reiterated their commitment to “continue to provide, in coordination with like-minded partners and allies, comprehensive political, financial, economic, humanitarian, military and diplomatic support to Ukraine and its people”. However, crucially, no agreement was reached on how the necessary funds would be mobilised.

There is strong support for using frozen Russian assets to assist Ukraine, including from the coalition of the willing and the US. A proposal to provide Ukraine with a loan secured by these frozen Russian assets has been around for some time.

It has not been finalised due to two major obstacles. The first was Ukraine’s refusal to accept EU conditions that while some of the money could be used to buy weapons, none of the funds should be spent on procuring them from the US. The second, more critical, issue was a demand from Belgium – where most of the frozen Russian assets are held at the Euroclear securities depository – for robust guarantees that the burden for any Russian litigation and retaliation be collectively shared by EU members.

Despite all the signalling from the EU’s leadership in the run-up to last week’s gathering in Brussels that these two major obstacles to approving the loan were being overcome, the meeting ended with EU leaders postponing a decision to their next meeting in December.

At the end of a week of concentrated attention on Russia’s war against Ukraine, the outcome was therefore a repetition of recent behaviour. The Trump administration flip-flopped and the coalition of the willing produced little more than a statement of intent to continue their support for Ukraine. The track record of Kyiv’s European partners to slow-walk the necessary goods for Ukraine’s defence continues. There’s mounting evidence suggesting that they will not stretch themselves to go beyond securing Ukraine’s immediate survival.

Unsurprisingly, a credible pathway to ending the war with a just and stable peace is still lacking.