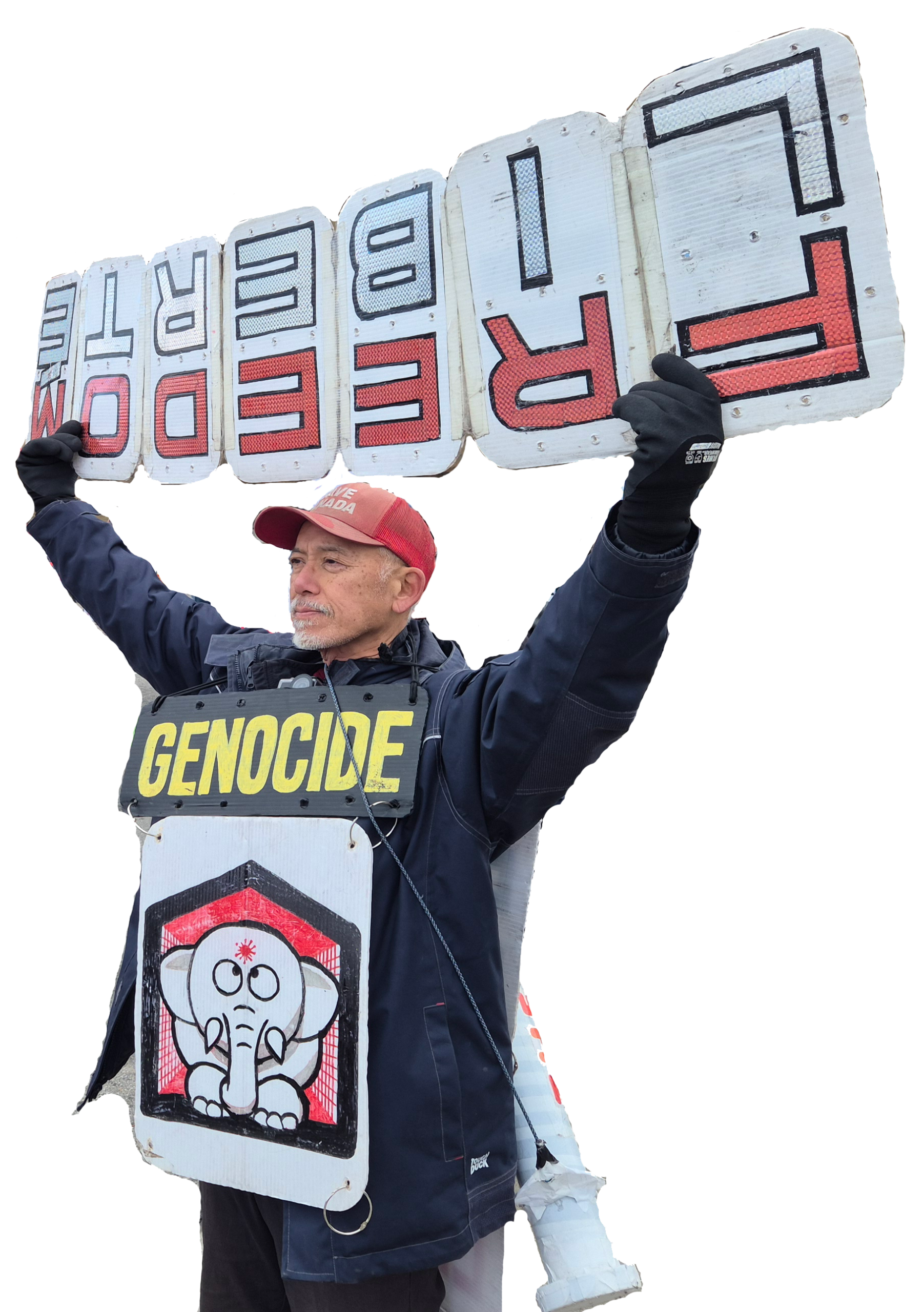

We find ourselves in the midst of a crisis of truth. Trust in public institutions of knowledge (schools, legacy media, universities and experts) are at an all-time low, and blatant liars are drawing political support around the world. It seems we collectively have ceased to care about the truth. The nervousness of democrats before this epistemic crisis is partly based on a widespread assumption that the idea of democracy depends on the value of truth. But even this assumption has a cost. Sadly, the democratic tendency to overemphasise the value of truth enters into conflict with other democratic demands. This leads us into contradictions that become fodder for the enemies of open societies. Philosophers have presented several arguments for this connection between truth and democracy. The most widespread is also the crudest: democracy stands for all the things we like, and truth is one of them. But there are more sophisticated ways to make the point. The German philosopher Jürgen Habermas argues that a healthy democracy has a deliberative culture and deliberation requires “validity claims”. When we talk about politics, we must bother to try and make sure what we say is true. Maria Ressa, a Filipino journalist and a Nobel peace prize laureate, similarly argues that democracy needs truth because: “Without facts, you can’t have truth. Without truth, you can’t have trust. Without all three, we have no shared reality, and democracy as we know it – and all meaningful human endeavours – are dead.” But do we really need truth to share a reality? In practice, most of our experiences of shared realities are not involved in truth. Think of myths, neighbourly feeling, or the sense of community, perhaps even religion and certainly the ultimate shared reality: culture itself. It would be hard to argue that we share in our community’s cultural reality because our culture is true or because we believe it to be true. Protesters call for Donald Trump to be removed from office and convicted. EPA/Luke Johnson Some might argue that democracy is bound to truth because the truth is somehow neutral. Of course, populist suspicion of experts is often couched in democratic language: the value of truth is meant to support a so-called tyranny of experts. But a key point here is that experts who aim to tell the truth, unlike liars or post-truth populists, have to be accountable. They are subject to the rules of truth. Democracy is therefore potentially more bound to accountability than it necessarily is to truth. ‘Meaningful human endeavour’ Be that as it may, the problem remains that, as Ressa and Habermas themselves recognise, the point of democracy is to promote “meaningful human endeavours”. Democracy is in the business of building a world in which humans can live humanly. And this, crucially, cannot be delivered by truth alone. A truly human life demands not only knowledge of facts about reality, but also a subjective understanding of the world and of one’s place in it. We often forget that although they often go together, these two requirements can also conflict with each other. This is because truth deals in facts while meanings deal in interpretations. Understanding, unlike knowledge, is a matter of how we look at the world, of our thinking habits and of cultural constructs – chiefly identities, values and institutions. These things fulfil their function of making us feel at home in the world without making any claim to truth. All too often, the democratic spirit disqualifies these things as prejudice and superstition. The champions of democratic truth would do well to remember that the world democracy tries to build is a world of meaningful human endeavour, not just dry knowledge and fact-finding. Current events have illustrated that overlooking this has dire political consequences. The insistence on truth and devaluation of meaning has led to the well-known modern depression often described as a sense of alienation – a breaking of social, historical and traditional bonds with each other and with ourselves. This alienation has provided a feeding ground for populists and anti-democrats, who present themselves as a corrective to the crisis of meaning. It is not for nothing that the recurring themes of contemporary populism are those of belonging, tradition, identity, origins and nostalgia. We are experiencing a crisis of truth – but we are also confronting a crisis of meaning. When we overemphasise truth over and against meaning, we foster a sense of alienation and deliver the public into the hands of its enemies. We might instead recall that a commitment to truth is only one, very partial condition for a truly human life, among many others, and build our democracies accordingly. Want more politics coverage from academic experts? Every week, we bring you informed analysis of developments in government and fact check the claims being made.Sign up for our weekly politics newsletter, delivered every Friday. This article contains references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and this may include links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

Is democracy always about truth? Why we may need to loosen our views to heal our divisions

Date: