“Howard’s Stand: Loyalty to Truth, Defiance to Power”

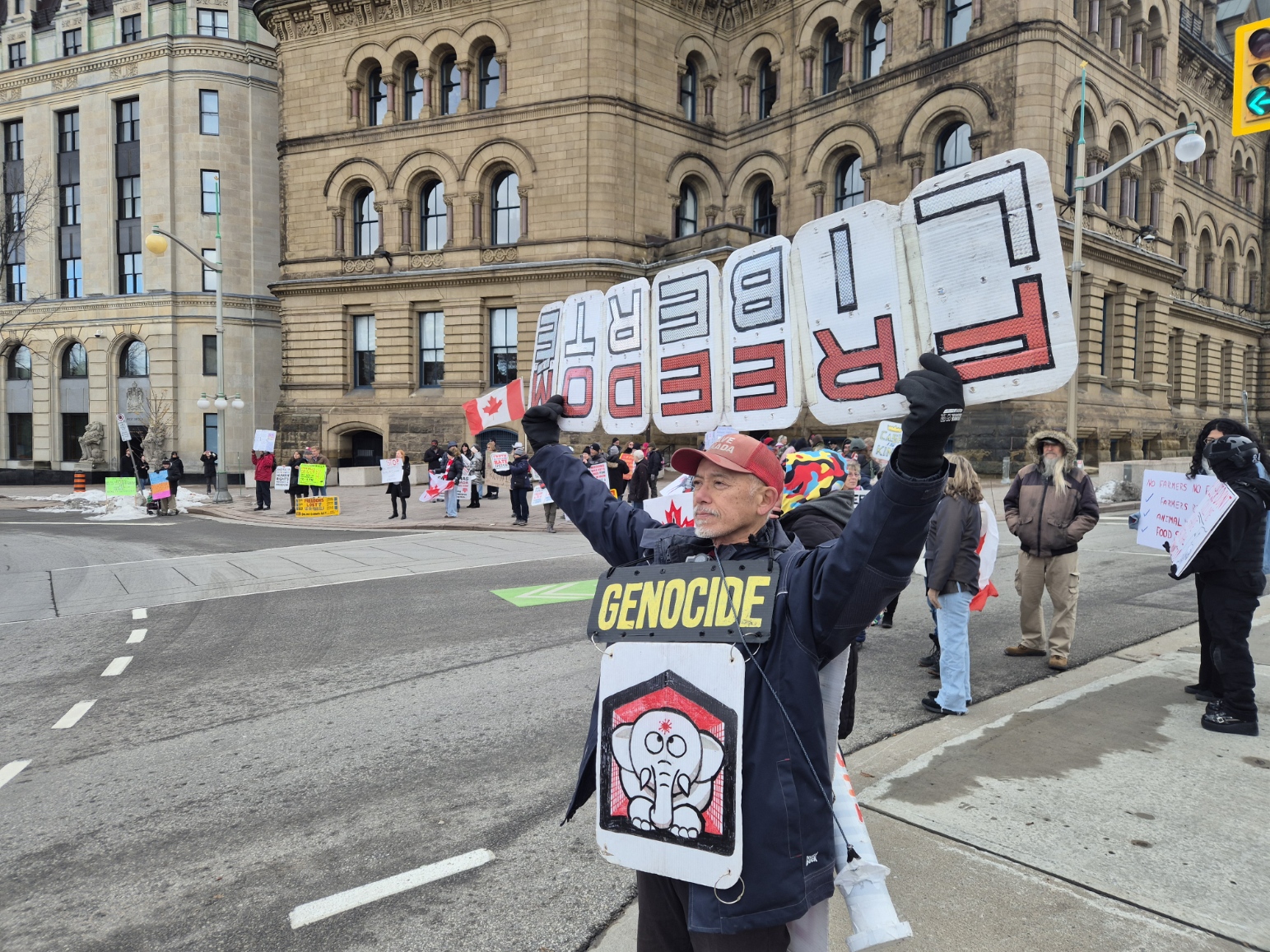

Howard stands tall on Parliament Hill, a lone figure against the cold Ottawa wind. His voice carries not just words, but conviction—unyielding, unafraid. He is the kind of protester who embodies resilience, a man who refuses to be silenced by indifference or power. Each step he takes across the stone grounds is a reminder that courage is not measured by numbers, but by the strength of one heart willing to stand for justice. Howard is not just protesting—he is defending dignity, a sentinel of conscience in the shadow of the nation’s halls of power.